By Ethan Rohrbach

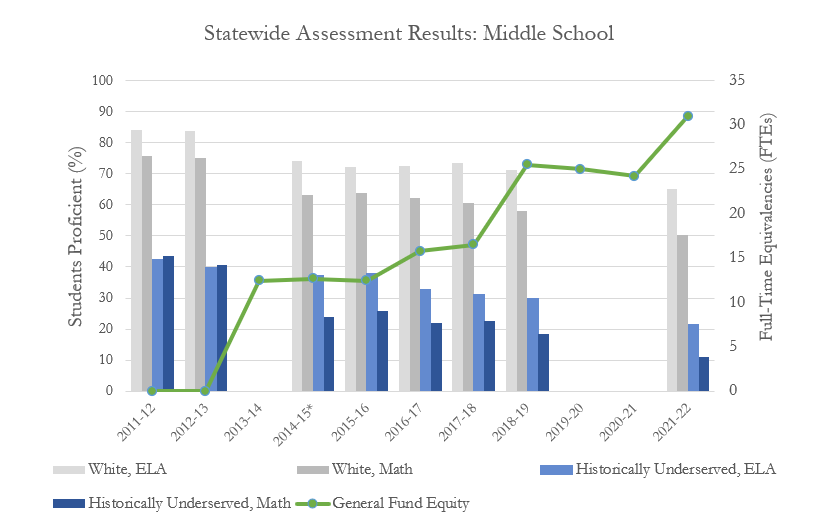

For decades, Portland Public Schools (PPS) has tried to close the “achievement gap” between white and non-white students. “Race,” they wrote in their 2013 Racial Education Equity Policy, “must cease to be a predictor of student achievement and success.” To do this, they began dedicating 8% of their yearly budget to General Fund Equity. This fund has taken various forms, first as “action plan” reporting, then as professional development training, now as “transformative curriculum and pedagogy” through a Racial Equity and Social Justice (RESJ) Lens. Funds are directed selectively toward inner-city schools with more racial minorities, like Jefferson High School.

After 10 years, it’s still not clear what this has accomplished. The district’s Citizen Budget Review Committee routinely wants to know how specifically PPS uses these mechanisms to meet their equity goals. The answer is more social workers and updated curricula, but these ideas seem no different from non-equity-related programs.

These supposed remedies for the achievement gap also appear disconnected from statistical reality. In middle schools, as General Fund Equity payments increase with the district’s budget, test scores for “historically underserved” students continue to lag about 40% behind white students in English Language Arts (ELA) and math. This is especially true for PPS’s “focus” schools in the inner city. Meanwhile, test scores for all students continue to decline.

Portland Public Schools can celebrate improving graduation rates, but not much else. Instead of following the same old strategy, PPS should get creative. More alternative schools could incentivize students, including non-white students, to improve their academic performance. The result: educational equity, what the district wants.

Ethan Rohrbach is a Research Associate at Cascade Policy Institute, Oregon’s free market public policy research organization.