By James Swyter

In 2015, representatives from Portland Public Schools (PPS) gave a presentation to the Portland City Council on discipline issues at the state’s largest school district. The presentation provided data showing that minority students were suspended and expelled at higher rates than other students.

Instead of examining why this gap existed, PPS simply pledged to reduce the disparity. The District promised to reduce the suspensions of minority students by 60% and the suspensions of other students by 40%.

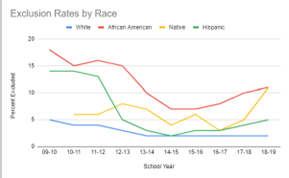

It was a promise that the District could not keep. Over the next four years, the racial gap for exclusions actually became larger by a significant amount:

The problem with the PPS promise was that it assumed that many of the District’s own employees were racist, and that such discriminatory behavior could be changed through better management. This is implied in the PPS Board policy on discipline, which states:

“The District recognizes that some students experience disproportionate disciplinary actions in response to their behavior….The District recognizes that unconscious biases can impact disciplinary decision-making.”

There is no evidence to support the claim that unconscious bias has been the cause of the racial gap in discipline. Neither the presentation to the city council nor the PPS discipline data web page contain any information about the students’ behavior that led to the disciplinary actions.

There is often a complex story behind the events that lead to a school punishment. Sometimes the school has no choice but to issue suspensions, such as in the case of PPS students who drove around shooting students with gel guns. Aggregated statistics don’t show what teachers and administrators are dealing with or student conduct leading to punishment.

Research shows many factors account for racial disparities in school discipline, including family life, environment, and culture. For example, the U.S. Department of Education records the number of self-reported fights into which each student becomes involved. Male students get into more fights than female students, 9th graders get into more fights than 12th graders, and Black students get into more fights than white students.

This corresponds with the data PPS presented to the city council: Male students receive more exclusions than female students, and Black students receive more exclusions than white students (PPS did not provide grade-level information).

Since 2014, PPS has implemented “restorative justice” programs to try to reduce the racial gap and the overall suspension rate. Restorative justice is considered an alternative to suspensions and expulsions and has been growing in popularity in school districts. Instead of punishing unacceptable behavior, restorative justice programs encourage students to resolve conflicts on their own and in small groups.

These programs at PPS have done little to reduce the racial gap. Restorative justice has decreased the overall suspension rate, but the racial gap remains. During the 2009-2010 school year, 7% of PPS students faced out-of-school suspensions or expulsions. Minority students faced these punishments about three times more frequently than other students.

Nine years later, during the 2018-2019 school year, 4% of PPS students were given suspensions or expulsions, and minority students were four times more likely to receive them.

The District’s focus on restorative justice has actually increased the racial gap in exclusions, suggesting that the difference in outcomes is beyond the control of teachers or administrators.

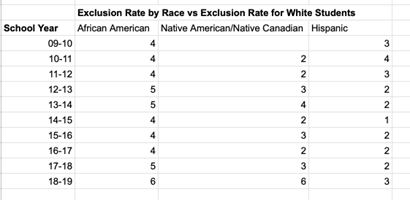

Exclusion rates as a relative ratio. For example in 2018-2019, African American students were six times as likely as white students to be excluded.

School personnel must make disciplinary decisions based on the facts of individual cases. Not suspending unruly students can have adverse consequences for the rest of the school. In November 2021, students at Roseway Heights Middle School walked out to protest ongoing sexual harassment among students. Students claimed teachers and administrators weren’t doing enough to stop the behavior.

During the walkout, fights broke out among students. One parent told KGW that “there were kids being chased by mobs of other students and hit,” and, “My daughter witnessed that firsthand. There’s a lot of racism going on. There were fights inside of the school. There were fights outside of the school.”

Although the Oregon Constitution guarantees all students a free education, it does not mean that individual students are guaranteed a seat in specific classrooms. PPS should adopt the philosophy that learning from great teachers is a privilege, not a right, and that privilege can be revoked if student behavior violates school norms.

In order to make that philosophy workable in practice, PPS should also offer parents a partial refund if students are excluded. Sometimes the school assignment is just a bad fit. If the money follows the child, the Constitutional promise of a free education will be fulfilled, while allowing teachers to maintain order in their classrooms.

James Swyter was a research associate at Cascade Policy Institute during Cascade’s 2022 Summer Internship Program. Based in Portland, Cascade Policy Institute is Oregon’s free market public policy research organization.