By Eric Fruits, Ph.D.

Oregon public school students are not likely to return to their classrooms this fall, with Portland Public Schools bracing parents for at least a semester of online classes. Even if they return to campus, PPS students face a two-day-on, two-day-off schedule. The uncertainty and chaos partially explain the results of a June survey conducted by USA Today and Ipsos that reported 60% of parents are likely to continue homeschooling this fall even if schools reopen. If a large portion of the population opts out of public schools this year, what happens to all that money?

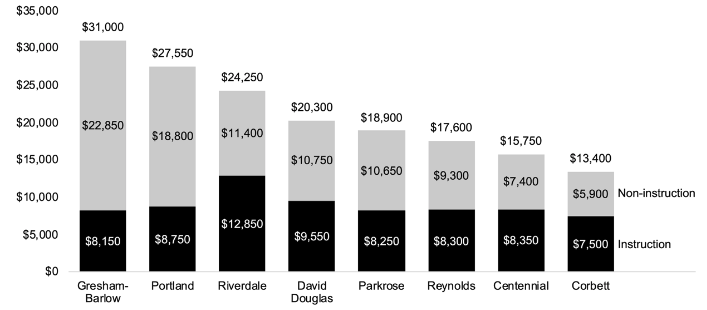

Funds for Oregon schools come from a complex mix of state, local, and federal sources. On average, school districts receive about $10,500 per student from the State School Fund. The figure below shows that districts in Multnomah County spend about $8,600 per student in instruction, which accounts for about half (or less) of total public school spending. If students aren’t getting instruction from their public schools, they should get that money back to receive instruction elsewhere. Imagine what families could do with $8,600 a year to spend on educational expenses.

Total expenditures per student (ADMr)

Multnomah County school districts, 2019-20 budget

Source: Multnomah County Tax Supervising and Conservation Commission

Source: Multnomah County Tax Supervising and Conservation Commission

Because district funding depends on how many students attend school in a district, public schools have a keen interest in maintaining or expanding public school enrollment. In written testimony to the legislature, the state’s teachers union and school employees union opposed increased enrollment in online charter schools. They claimed that increased enrollment in charter schools would “reduce the funding that districts need.” Governor Kate Brown closed online charters along with brick and mortar schools in part because increased charter enrollment would “impact school funding for districts across Oregon.” For the unions and the governor, students are not kids seeking an engaging education, they are merely a source of funds to fuel the public school system.

Public education should fund students’ education instead of the education system. The money should follow the child, wherever he or she may choose to go. If a student chooses the public school, then the funds should flow to the public school. If a student chooses a private school or a charter school, then the funds should be used to offset those costs. Families of homeschoolers should receive funding to offset their out-of-pocket education expenses. If that seems obvious, that’s because it is obvious.

Think of it as a form of money-back guarantee. If you’re happy with your public school, stay there. But, if the public school isn’t working for your child, you should be able to get your money back and spend it where it works. In July, Education Secretary Betsy DeVos suggested rather than “pulling funding” from schools, the government is considering “allowing families…[to] take that money and figure out where their kids can get educated if their schools are going to refuse to open.” Many parents will find $8,600 to spend on education can go a long way if they shop around.

This isn’t a radical idea. It’s how higher education works for millions of college students. They can take their Pell Grants, GI Bill funds, and other financial aid to just about any school they want. Why is K-12 “financial aid” contingent on attending a bureaucratically assigned public school?

The practice of assigning students to schools based on street addresses is inherently unfair. Wealthier neighborhoods have better-funded schools with better measures of student achievement, while poorer neighborhoods have run-down schools with dismal academic performance.

The pandemic has exposed our state and local governments as broken. They only “work” during a booming economy, when wasted money and misplaced priorities are obscured by widespread prosperity. But when effective public services are needed most, our government institutions have ground to a halt and, in some cases, made things worse. Now more than ever, families should control their education funds to find schooling solutions that match their children’s needs, their work schedules, and their health concerns. A money-back guarantee of $8,600 per student would go a long way toward finding those solutions.

Eric Fruits, Ph.D. is Vice President of Research at Cascade Policy Institute, Oregon’s free-market public policy research organization.

Click here for PDF version:

Richard

Another question raised by the numbers is how does Riverdale, whose educational results are among the best in Oregon, manage to spend to spend so much more of available funds on instruction compared to the other districts? Portland and Gresham-Barlow have more funds available but only spend two-thirds as much on instruction as Riverdale. Starting with even less money than Portland David Douglas manages to spend more on instruction which should lead to better student achievement.

Gordon J. Fulks, PhD

Good Grief, Dr. Fruits, why is Gresham Barlow spending $22,850 per student per year on “non-instruction,” when the adjoining district of Corbett spends only $5,900?? That is outrageous. Why the enormous inequity?

And the other obvious question is what is “non-instruction spending anyway? Football? Admin? Buildings?

I pay property taxes to both districts, but Corbett with the least “non-instruction” and “instruction” spending produces by far the best outcomes, according to my sources. Of course, Corbett always wants another bond issue, and we keep saying no. Spending actually seems counterproductive!