Summary: HB 2229 will allow counties throughout the state to take a fresh look at their designation of agriculture and forestry lands. Before that happens, there needs to be further consideration of all the elements needed for commercial agriculture and forestry to be viable. Soil type is not the only thing upon which to base a land designation.

Oregon’s land use regulatory system was established under Senate Bill 100 in 1973, and the land use Goals of the Land Conservation and Development Commission (LCDC) were adopted in 1975. Under the land use system, LCDC forced counties to zone over 96% of all rural land in the state into highly restrictive “farm” and “forest” zones, without regard to farm and forest productivity, economics or the property rights of the landowners. Basically, it was zoning to provide open space. This zoning is still in place.

For example, about 16 million acres are zoned into highly restrictive “Exclusive Farm Use” zones; but less than 5 million acres are farmable, and only 2.8 million acres are producing agricultural crops. The remaining 11 to 13 million acres are generally unsuitable for farming and useful only for grazing at best. Grazing generally provides a very low return on a per-acre basis. Much acreage within the 9 million acres zoned “forest” is also nonproductive or low-productive. Worse yet, over the years, the state legislature and LCDC forced counties to impose more and more restrictions on dwellings, land divisions and other uses.

Since the passage of Senate Bill 100, three initiative measures (in 1976, 1978 and 1982) were launched to overturn the statewide land use planning system, but all failed. Efforts to secure reforms in the legislature did provide some modest changes, but the overall rural zoning system is still in place.

Then, in 2000, a new approach was used. Measure 7 was placed on the ballot amending the constitution to require just compensation for landowners who lost property value due to downzoning of their property after they acquired it. This measure passed but was ruled unconstitutional by the Oregon Supreme Court for technical reasons. So, in 2004 Measure 37, a statutory approach, was introduced and passed. It, too, required all levels of government to compensate landowners for lost property value due to zoning restrictions imposed after they acquired their property or to waive the restrictions.

Most recently, the state legislature drafted and enacted Measure 49, which was referred to and passed by Oregon voters. Unfortunately, Measure 49 took away much of the relief Measure 37 provided for landowners.

This 36-year history of over-regulation, unsuccessful reform efforts and measures being passed and then challenged, overturned or decimated has frustrated landowners. It is very difficult to bring about broad, sweeping changes to land use laws in the current political climate.

But now there may be an opportunity to make some changes on a county-by-county basis. In the 2009 session, Oregon legislators passed House Bill 2229, which allows (but does not require) counties to reassess their very restrictive rural land zoning and bring some flexibility to land uses, primarily by allowing more land divisions and rural dwellings.

This would increase property tax revenues and provide much-needed economic benefits for counties, without any adverse impacts on farm and forest operations.

But counties still will have to comply with land use laws and LCDC Goals and rules, which will be barriers to change. This is where additional work needs to be done to allow counties to secure significant benefits from the process. Some Goals and rules need to be revised to allow more flexibility.

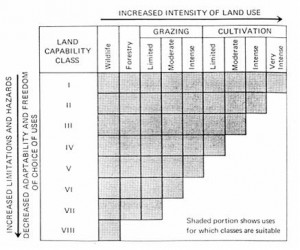

One area that needs to be addressed is criteria for designating agricultural land. Currently, lands that have a soil classification of I–IV in western Oregon and I-VI in eastern Oregon (as defined by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service) are to be designated “agricultural land.”

This should be revised for the following reasons. Much of this land has little or no value for agriculture. There are many factors other than soil quality that should be considered in designating agricultural land, such as water for irrigation, weather and infrastructure. There is much variation in agricultural capability of rural land throughout the state. Also, under current regulations, if a parcel consists of merely 51% of soil in those classes, then the entire parcel is considered farmland. An 80-acre parcel could consist of only 41 acres of so-called farmable land. What can be done with the other non-farmable 39 acres? This regulation should be revised to allow more uses on the 39 acres that are unproductive, such as allowing a home for a family member or to sell the home on its own parcel.

House Bill 2229 includes some overarching principles that provide justification for modifying state policies, including sustaining “a prosperous economy” and equitably allocating “the benefits and burdens of land use planning.”

Despite the barriers to securing rural land use reforms under House Bill 2229, landowners should actively urge county commissioners and planning commissions to take advantage of the process. Counties that choose reform can reveal the extent of rural land miszoning and reduce barriers to sensible land use.