By Thomas Tullis

On July 17, Governor Kate Brown signed Senate Bill 81, the “Oregon Promise” legislation that allocates $10 million to a “free” community college tuition program for Oregon students.

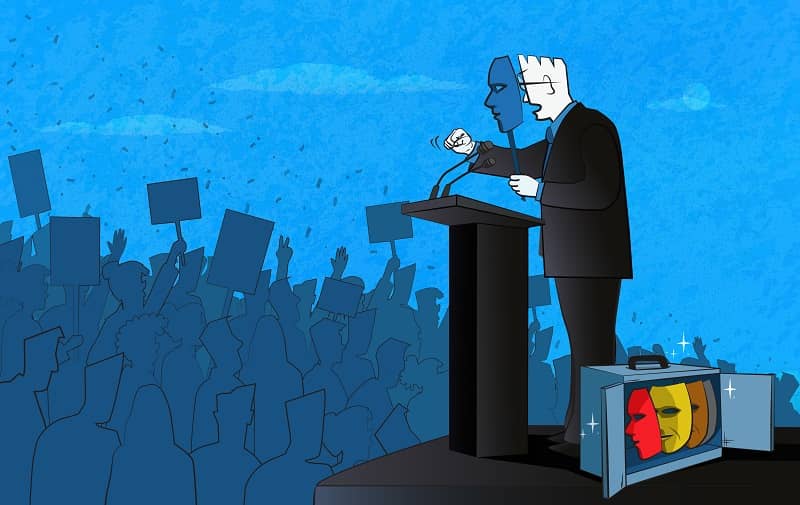

As a current undergraduate at University of Oregon, I understand the importance of education and the problem of exponentially rising tuition costs. With college tuition increasing ten-fold over the last three decades, Oregon lawmakers likely have good intentions in implementing State Senator Mark Hass’s “Oregon Promise” idea. Good intentions, however, are not enough to make it good policy. Unfortunately, Oregon Promise will do little to solve the problem of tuition affordability. Rather, “free” tuition will actually hurt the cause because government subsidies are a major factor in the high cost of college tuition.

“Free” tuition is a “band-aid policy” because it ignores the real problem of rising costs of higher education. A basic understanding of economics leads to the conclusion that state-funded education encourages schools to raise tuition because they are guaranteed demand. Government subsidies (tax credits, loans, and grants) ensure that colleges can raise tuition and increase their spending, rather than cut costs. Even the government recognizes these unintended consequences: A recent Federal Reserve study showed that government grants and loans have caused a 65% increase in tuition. Oregon Promise won’t make college more affordable; instead, it will allow colleges to increase tuition.

Essentially, “free” education actually ends up costing more. It just doesn’t affect the student’s price directly. Tuition costs don’t go down; instead, the cost is diverted from the student to the taxpayers. Under the Oregon Promise law, it very well may be that Oregon college graduates who already have a burden of student debt will absorb the cost of the new “free” tuition.

As outlined in a recent article in The Oregonian, the legislation has already been criticized for its “last dollar” award calculation structure, by which low-income students eligible for other forms of aid could receive less Promise funding than higher-income students without as much aid. With a tuition rise inevitable, due to the guaranteed demand that these programs provide, those who are denied Oregon Promise money could end up paying even more in tuition.

The policy is negligent in other ways, also. While the opportunity to attend college is important, there are other routes to success for those who don’t fit into the traditional model of classroom higher education. College is not the only way for recent high school graduates to invest in their futures and acquire education and skills. The new Oregon policy encourages and supports only one method of education, while ignoring the importance and value of trade school, apprenticeships, and other paths to a career.

The Oregonian quotes national expert Dr. Sara Goldrick-Rab, a Wisconsin-Madison professor of educational policy studies and sociology, as claiming that “Oregon’s ahead of the whole rest of the country here, at No. 2” [with a free tuition program]. What she doesn’t recognize is that the only education statistic in which Oregon leads the nation is our #1 lowest high school graduation rate. The real solution to tuition affordability would be to free the education market from further government intrusion. Rather than conjuring up a government-funded 13th and 14th grade, Oregon needs to first look closely at our failing K-12 system. Lawmakers should focus on allowing a free market to exist for education providers at all levels, so they can compete on quality and price. A free market in education would help students be better prepared for college—and be able to afford it, too.

Thomas Tullis is a research associate at Cascade Policy Institute, Oregon’s free market think tank. He is a student at the University of Oregon, where he is studying Journalism and Political Science.